By stubbornly applying a ‘dirty-hands-on’ approach to this and other early cases, he ultimately developed the submersible mixer. Soon after this, a new Marketing Director at Flygt developed a plan for selling these mixers. The plan called for the company to systematically develop the know-how necessary to apply this unique product in different business areas. The submersible mixer now accounts for 5% of Flygt’s global turnover.

In 1977 ITT Flygt introduced the world’s first submersible mixer. The man behind its development was Hjalmar Fries. Hjalmar was trained as a design engineer and from the 1960’s worked with both marketing and product developmentt. Early in his career he was involved in conducting trials of a new wastewater pump designed for municipal treatment plants. The trials were being carried in a tank located in a farming area, close to ITT flygt’s factory in Lindås, in southern Sweden.

The Farm Market?

A local farmer suggested to Hjalmar that the wastewater pump might be used for handling the manure that his dairy cows produced. The manure was discharged into a thousand-cubic-meter tank. It then had to be removed from the tank so that the farmer could spread it over his land to fertilizer the crops he grew. The farmer’s casual suggestion got Hjalmar thinking about farmers as a potential market. Since he’d now become interested in farming, Hjalmar set up a trial to pump the dairy farm’s manure and installed a pump and some other equipment in a tank of farm manure.

«It was a much bigger challenge than domestic sewage – farm manure gets a lot more contaminated with stuff like straw, bits of wood and everything imaginable from chains to bits of farm machinery. And, sure enough the pump got blocked.» But being an enthusiastic product developer, Hjalmar did not abandon the project. He and his team developed an impeller which could cut through the straw and other debris, which would otherwise clog the pump. (This was an early version of Flygt’s ‘NevaClog’ pump.)

Using complaints

Twenty of these prototype ‘manure’ pumps were sold to farmers in Scandinavia. «Nearly all of them came back with complaints,» Hjalmar recalls. «This is a crucial stage in new product development. A positive response to it (which can be called the ‘Case-Based’ approach) is to send the product designers to look at the customer’s problem. In this case, this meant going to each farm and spending at least half a day there – being introduced to the farmer’s wife and animals, taking coffee or beer with him, etc. This is what I mean by looking at a problem – and, fortunately, since I had influence in the marketing department and my own budget, I was able to do this in this case. And, when you do this, almost invariably, you discover that the problem is not what you expected – and the solution fairly obvious: in the case of the manure pump failures, I climbed into the tanks and stood on it! The problem was a lack of adequate mixing. The pumps were pumping out the liquids and leaving the solids behind.»

Addressing mixing

Hjalmar now became very interested in the problems of mixing, particularly with regard to manure. He also employed an agricultural engineer to help with this research. «We realized that efficient mixing could offer two enormous benefits to farmers: firstly, they would be able to maximise the use of the manure produced on their own farm – in some cases I discovered that farmers were only able to use a third of the volumes in their tanks. Increasing this useable volume would represent a considerable cost saving in replacing bought-in fertilizers. Secondly, effective mixing would greatly improve the fertilizing quality of manure: the solid part is carbon-rich while the liquid is rich in nitrogen. The ideal for fertilizer is a balanced mix of both.»

As a result of these ‘Case Visits’ Hjalmar and his team went on to develop the submersible mixer. «The key to this Case-Based approach to development is to use the customer’s problems as a design resource. Of course, when implementing this ‘dirty-hands-on’ approach, you still have to keep an eye on the bottom line – we were stubborn about pursuing the farm market because we knew it was potentially very significant. Once you’ve established that there’s significant demand in a new field of application, the task then is to thoroughly understand, ideally from direct personal observation, the business that these customers work in and the problems they confront.»

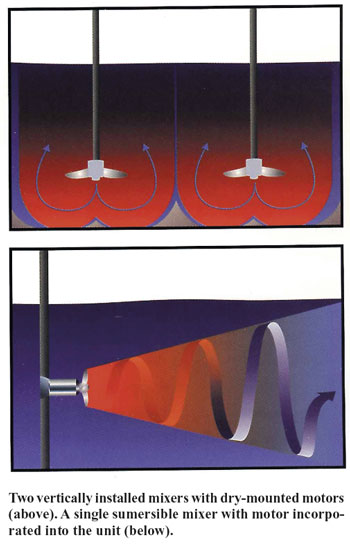

The submersible mixer is able to generate a ‘jet flow’ inside a tank. The mixer can be positioned to direct the flow, ensuring that there are no ‘dead corners’ in the tank. By providing farmers with a package of mixer-plus-pump, the manure handling problem was solved. Having created the submersible mixer, it then became apparent that it had many other applications: Flygt’s sales force, with its well developed networks in municipal waste water treatment, immediately began to sell it to sewage plants.

A fish farmer calls

Hjalmar also began to investigate the mixing processes required in the pulp and paper industry. In addition, fish farmers, quite spontaneously began buying submersible mixers to generate water exchange in their fish pens. (This is often necessary both to raise the oxygen content inside the pens and to expel waste products from the fish.) «I got an enquiry from Norway; a fish farmer was asking if we had any smaller mixers. At that time the smallest we made was powered by a 14 kW motor. This was really too big for fish farm applications. We established that what they really needed was a 2 kW unit. I told him that if he ordered 30 of them, we’d produced it – which lead to the introduction of our small mixer range.» Today the submersible mixer is used for applications in almost the same very broad range of industries as the pump.

Marketing the mixer

Leif Carlsson came to ITT Flygt (from Atlas Copco) as Marketing Director in 1983. One of his first major tasks was to formulate a marketing strategy for the submersible mixer. Prior to this, Flygt’s sales and marketing of this product had been pretty much erratic and reactive. «There were a number of barriers to be overcome for product acceptance; firstly, there was still scepticism regarding the use of a submersible motor – though we’d made quite a lot of progress on this issue in connection with the submersible pump. Secondly, submersible mixers require motors which are 30% to 50% smaller than those for an equivalent conventional mixer. Even though this means a corresponding energy saving, potential customers needed a lot of persuading that the smaller motors could actually produce the same mixing effect. As a company the main problem we faced was that, while we were well-known as a pump company, we had no reputation in mixing – we had to build this from scratch.»

«We also knew that our competitors would not be far behind us. The technology did not protect us – if you can make a submersible pump, you can make a submersible mixer and we already had a number of strong competitors on the pump side. So, we decided to differentiate ourselves on the basis of know-how about how to apply this new technology. Conventional, dry-mounted mixers had been around for a long time and there were a number of well-established ‘rules of thumb’ about how to use them. Submersible mixing is completely different, so these rules didn’t apply and since the product was brand new, no body really knew how to apply it. So, we decided to find out and turn this knowledge into a competitive edge.»

Case-specific field trials

Having accumulated a theoretical and experimental knowledge base, Flygt then set up two major field trials; one for wastewater treatment applications and one for the pulp & paper industry. «We took wastewater first because this was an application where we already had a strong brand as a pump maker,» Leif Carlsson points out. The wastewater trials were conducted at a treatment plant in the UK. The other trials were held at a small, experimental production line operated by the Swedish Pulp & Paper Institute in Stockholm. «Our motivation in running these trials was to establish databases for submersible mixer sizing parameters in, respectively, wastewater treatment and pulp & paper applications. This knowledge put an effective tool into the hands of our sales force.»

«In other application areas, such as fish farming, mining and agriculture, the parameters don’t need to be as precise as they do in process industry. Here we learned a lot from our customers,» adds Lars Frisk. «Many customers seized on the submersible mixer as a potential solution to a problem they’d been living with for some time and were willing to try it out even without any prior knowledge of how to apply it in their application,» notes Leif Carlsson. «Its use in spray painting systems in automotive manufacturing is an example of this.» Another, even more exotic, application was the use of the submersible mixer to keep water free from ice in sub-zero temperatures. «Frankly speaking,» says Lars Frisk, «some of these applications were more trouble than they were worth, but we didn’t know that when we started working on them. The whole market was pretty much ‘virgin territory in those days - you staked a claim to an area and worked it to see if it held anything of value – and, of course, other people could come in and do the same.»

«We can say that the submersible mixing really became an established technology in our first target area, wastewater treatment, around 1990,» says Leif Carlsson. «We can say this with some confidence because it was at about this time that our competitors started seriously trying to move into this market. Pulp and paper is maybe a little bit behind in this development, but is definitely on the way. A distinct problem here is that our sales are mainly based on directly replacing a conventional mixer with a submersible one and process industries are notoriously conservative about making this sort of technological change.» Lars Frisk adds that, «at the beginning we thought that in order to succeed in pulp and paper we had to be a ‘total mixer supplier’; in other words, that we needed to offer a product for each mixing application in the industry. Now, however, we’ve realised that it’s OK for us just to concentrate on the mixing niches where submersible is the best solution – though, again, this is something we’ve learnt with experience over the years, and I would say it also applies to other industries. We now have much more of a ‘niche applications’ strategy – though there are still lots of potential applications that we really haven’t addressed at all yet.»

«Adopting this ‘know-how’ strategy to market it meant that we got deeply involved in trying to understand the chemical and biological process of wastewater treatment”, says Leif. “This lead us to adopt other new products, such as aeration diffusers, and also turned us into much more of a ‘systems know-how’ company, than simply a manufacturer.» << (photos: ITT Flygt)

This article is an edited extract from Dr Minett’s book “B2B Marketing – a Radical New Approach for Business-to-Business Marketers”, Financial Times/Prentice Hall, 2002.

By Steve Minett, PhD